Section11Further Reading

Subsection11.1Specialized Subdivisions

In a longer work you might wish to have some references on a per-chapter basis, or similar. You can make a “references” subdivision anywhere to hold bibliographic items, and you can reference the items like any other item. For example, we can cite the article below [11.2.2, Chapter R], included an indication that a specific chapter may be relevant.

Subsection11.2References

These items are here to test basic formatting of references.

An online, open-source offering.

This is a conclusion, which has not been used very much in this sample. Did you see the the second reference above has a short annotation? So you can make annotated bibliographies easily.

Subsection11.3Exercises

1

No problem here, but the next two are in an “exercise group” with an introduction and a conclusion. The two problems of the exercise group should be indented some to indicate the grouping.

In the next two problems compute the indicated derivative.

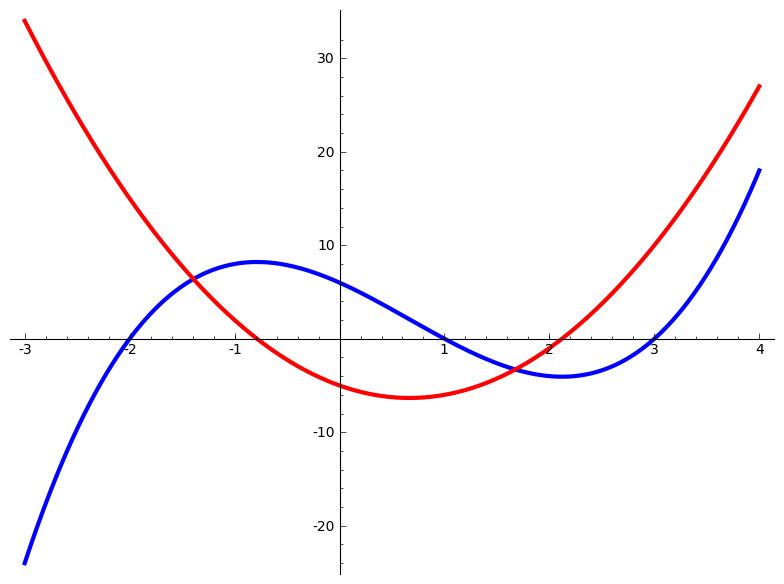

Use a sidebyside element to insert a relevant image, or tabular, or other un-numbered item tht does not fit in a sentence.

You could “connect” the image above with the exercises following as part of this introduction for the exercisegroup.

2

\(f(x)=x^3\text{,}\) \(\frac{df}{dx}\text{.}\) This sentence is just a bunch of gibberish to check where the second line of the problem begins relative to the first line.

We cross-reference the next problem in this exercise group. For the phrase-global form, the common element of the cross-reference and the target should be the exercises division, and not the enclosing exercisegroup: Exercise 3 of Exercises 11.3.

3

\(y = \cos(x)\text{,}\) \(y^\prime\text{.}\)

Note that the previous two problems used very different notation for the function and the resulting derivative.

4

Compute \(\int 3x^2\,dx\text{.}\)

5

One of the few things you can place inside of mathematics is a “fill-in” blank. We demonstrate a few scenarios here. See details on syntax in Subsection 4.7–the use is identical within mathematics.

Inside inline math (short, 4 characters): \(\sin(\underline{\hspace{1.818181818181818em}})\)

Inside inline math (default, 10 characters): \(\sin(\underline{\hspace{4.545454545454546em}})\)

Inside exponents and subscripts (2 characters each). In this case, be sure to wrap your exponents and subscripts in braces, as would be good LaTeX practice anyway: \(x^{5+\underline{\hspace{0.909090909090909em}}}\,y_{\underline{\hspace{0.909090909090909em}}}\)

Inside inline math (too long for this line probably, 40 characters long): \(\tan(\underline{\hspace{18.1818181818182em}})\)

-

So use inside a displayed equation

\begin{equation*} 16\log\space\underline{\hspace{3.636363636363636em}} \end{equation*}like this one.

-

Inside the second line of a multi-line display:

\begin{align*} y &= x^7\,x^8\\ &= x^{\underline{\hspace{1.363636363636364em}}} \end{align*}

Subsection11.4More Exercises

1

This is not a real exercise, we just want to explain that this is another subsection of exercises, which has two consecutive exercise groups.

Introduction to first exercise group.

2

Only exercise of first group.

Conclusion to first exercise group.

Introduction to second exercise group.

3

First exercise of second group.

4

Second exercise of second group.

Conclusion to second exercise group.

An <exercisegroup> can have a cols attribute taking a value from 2–6. Exercises will progress by row, in so many columns. On a small screen, the HTML exercises may reorganize into fewer columns.

5

\(1+2\)

6

\(3+4+5\)

7

\(5+6\)

8

Add seven to eight.

9

\(9+10\)

This feature was designed with short “drill” exercises in mind.